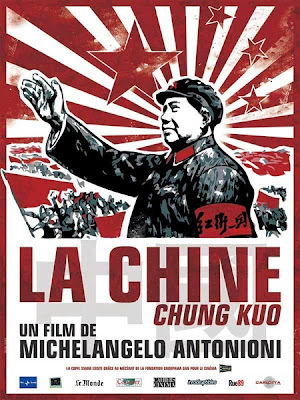

In 1972, during Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, Michelangelo Antonioni was invited by the People's Republic of China to direct a documentary about New China. Only permitted to visit certain parts of the country, the director traveled with his crew for eight weeks in Beijing, Nanjing, Suzhou, Shanghai, and Henan. The result was a three and a half hour long film, divided into three parts. Mao and his wife Jiang Qing disliked it so much that Michelangelo Antonioni was consequently charged with being anti-Chinese as well as counterrevolutionary. The movie was finally shown at Beijing's Cinema Institute 30 years later.

T

his documentary was taken in Chinese Cultural Revolution period, and is divided into three parts:

The first part contains some scenes in Beijing captured by the director, such as the famous Tiananmen Square, the Great Wall, the Forbidden City, Wangfujing, visible recess activities in primary schools arranged by the Chinese government, acupuncture production in hospital, factory workers’ family life and the status of the producers’ cooperatives, and so on.

In the second part, the director was arranged to Linxian, Henan province to visit the Hongqi Canal, collective farms and the ancient city of Suzhou and Nanjing, but he put large spaces on randomly observed Chinese expressions.

The third part is a brief observation of Shanghai by the director, from the streetscape to the birthplace of Chinese Communist Party, from new residential buildings to the Roll Lumbricus in colonial period, from teahouse to the large factory, from the Bund to the boatman on the Huangpu River. Relatively, the film reflected Shanghai people’s lives objectively.

In my eyes, this documentary is very quiet and the scenes move slowly. Instead of pleasing us and adapting to the illusions in our mind by cutting the lives, the film forced us to see life show itself slowly with its own rhythm.

Shooting conditions: Obviously, the route and the scene were designated and arranged in advance, and the freedom of the director is very limited. Under the fact of an overall false, a strong sense of reality was reflected from the film just by shooting techniques and some scenes by force and grabbing. We saw the gesture, facial expressions and manners of speaking of people in that era again. Antonioni did not meddle with the Chinese government by standing on the ideology. On the contrary, he knelt down and stared at the real life, making the real life penetrating by his film. Like Jia Zhangke, he knew how to explore the poetry of ordinary life. Those low, dark and even sneaking corners of life can become a poem because of staring, which is the Zen in hard life.

I think art and memory have the same process.

这部拍摄于中国文革时期的纪录片分为三个部分:

第一部分是导演在北京对一些场景的捕捉,有著名的天安门广场、长城、故宫、王府井,有中国政府安排的参加小学可见课间活动、医院的针灸生产、工厂的工人家庭生活、生产合作社的状况等。

第二部分是导演被安排去河南林县参观红旗渠、集体农庄、古城苏州和南京,但他却将大量的篇幅放在了随意观察的中国人的面孔上。

第三部分是导演对上海的短暂观察,从街景到中国共产党诞生地,从新建的居民楼到殖民地时期的滚地龙,从茶馆到大工厂,从外滩到黄浦江上的船户,相对客观地反映了当时上海民众的生活。

在我眼中这部纪录片的镜头很安静,移动缓慢,不是切割生活来讨好我们,来适应我们头脑里的假象,而是强迫我们去睁眼看生活,看它自己的节奏,自己慢慢的展现。

拍摄条件:很明显,路线是被指定的,场景是被安排好的,导演的自由度非常有限。只是在全盘虚假的算盘底下,仅仅靠拍摄手法和几个强拍抢拍的镜头,胶片中渗出一种强烈的真实感。我们重新看到那个时代的人们的动作,表情,说话方式。安东尼奥尼不是站在意识形态的高度指手画脚,他蹲下来,凝视,让生活自己从画面中渗透出来。和贾樟柯一样,他懂得发掘平凡生活的诗意。那些低下、灰暗、甚至委琐的人生角落,因着凝视,也能够成为诗,这是一种艰苦生活中的禅意。

我想艺术与记忆是同一个过程。

没有评论:

发表评论